History of the Kulla of Gjon Marka Gjonit

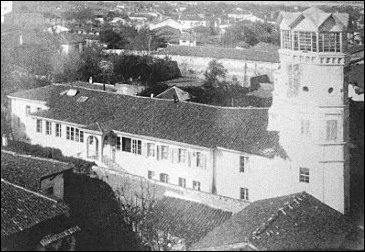

The “Kulla Markagjoni” was constructed during the mid-1800s by Bibё Doda (1820-1868), the Kapidan of Mirdita. The residence, measuring 819 square meters, was built in close proximity to the Jesuit Seminary, situated directly opposite on the street, in Shkodra. The current dimensions of the building and its surrounding gardens amount to a total area of 2,650 square meters. Nevertheless, the property was initially twice as large. In 1944, at the onset of communism, the regime seized the property and subsequently constructed buildings at the back of the house, resulting in the loss of a significant portion of the property.

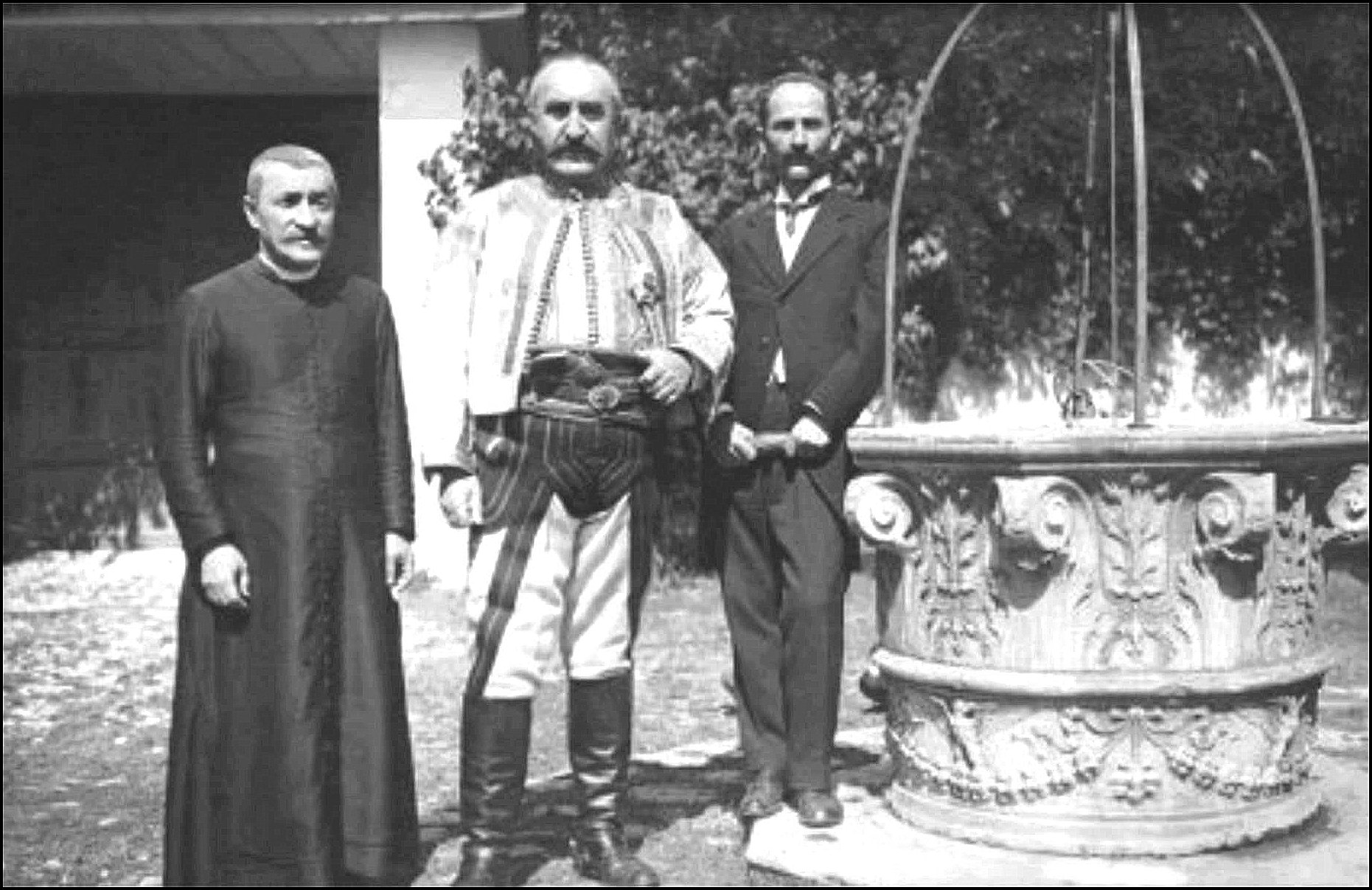

Born in Orosh, Mirdita, in 1860, Prengё Bibё Doda is the only son of Bibё Doda. Prengё and his sister Dava were brought up in Shkodra, where his father Bibё Doda had relocated. The environment encircling Prengё was a fusion of the traditions and culture of the Mirdita highlands and the education and culture of the city of Shkodra. Bibё Doda was assassinated in Shkodra in 1868 by poisoning; he was succeeded by his wife Margjela, his son Prengё Bibё Doda, and his daughter Dava. The Turkish government expeditiously extradited the young boy Prengё to Istanbul, leaving behind his sister and mother. His return did not occur until 1876. Following his involvement in the Albanian League of Prizren in 1878, he was once more exiled to Istanbul. He was not released until 1908.

Margjela, Prengё’s mother, embodied the qualities of leadership, intelligence, competence, and determination, which were indicative of her spouse. Despite not being formally involved in self-government, she exerted considerable sway over Mirdita’s decision-making processes via her son and the leaders in Mirdita. Following her son’s exile, Margjela, her daughter Dava, and her adopted daugther Marta continued to reside in the “Kulla” of Shkodra. She guarded her son’s position and, by extension, the legacy of Bibё Doda since her son’s exile in 1878, doing so with the grace and dignity befitting a princess.

Shkodra was struck by a catastrophic earthquake in 1905, which not only damaged the residence but also claimed the life of Prengё’s sister Dava. Prengё Bibe Doda, upon his return from exile in Turkey in 1908, commissioned the renowned architect Kolё Idromeno to renovate the residence and add a five-story structure to its south side, in response to the extensive damage caused by the earthquake. The tower was completed around 1910.

In 1913, two significant events transpired. Margjela Bibё Doda passed away and was interred in Shkodra; in September of that year, Prengё Bibё Doda wed Lucja Gjinaj. A new beginning for the Kulla. Sadly, Prengё Bibё Doda was assassinated in an ambush in Durrёs on March 22, 1919, without leaving any descendants behind. Following this, his wife Lucja remained in the residence for a period of time.

In accordance with the prevailing highland’s law of the time, the Kanun of Lek Dukagjini, the absence of male descendants meant that Prengё’s cousin Kapidan Marka Gjoni (1860-1925), the son of Gjon Marka Lleshi, was the subsequent in line of succession. This resulted in Kapidan Marka Gjoni inheriting the Kulla in Shkodra, in addition to other properties. Usufruct rights were granted to Lucja Bibё Doda until a future date determined by the heir apparent of Marka Gjoni, his son Kapidan Gjon Marka Gjoni.

Subsequent to Kapidan Marka Gjoni’s death in 1925, the property was entirely inherited by his son, Kapidan Gjon Marka Gjoni. A mutual financial agreement was reached between Kapidan Gjon Marka Gjoni and Lucja Bibё Doda a few years later, allowing her to vacate the premises and establish residence in an alternative location.

Kapidan Gjon and his family were able to eventually inhabit the house they had rightfully inherited. Aside from its residents, the house was a significant attraction in Shkodra during its heyday due to its size and elaborate architecture. In addition to receiving government officials and community members, it was frequently visited by a multitude of dignitaries from around the globe. Kapidan Gjon Marka Gjoni subsequently established his residence in Shkodra, where his younger children gained their education. The establishment of the “Independent National Group” of Shkodra in March 1944 by his son Kapidan Mark Gjon Marku, which served as the precursor to the anti-communist resistance movement, was directed and managed from the Kulla.

The dwelling comprised two stories of habitable area. The kitchen was situated on the ground floor, providing stair access to the first floor that housed the remaining spaces. The library, which was the most essential component of the dwelling, is located in close proximity to the tower on the south side of the residence. This location was visited by every dignitary and guest who had traveled to Shkodra to pay their respects to the Kapidans. During that period, the room was decorated with Persian rugs and antiquities, in addition to a wood-carved ceiling, elaborate wall panels, and a decorative bookcase. There are a total of twenty-five rooms in the residence. Located on the southern side of the house, the five-story tower was built, offering four stories of habitable space. A Venetian well sits on the north side of the house.

The communist regime seized the residence in 1944, subsequently destroying and pilfering every piece of furniture and accessory. The home was turned into the headquarters for State Security, later becoming government offices and, ultimately, a girls’ school. During these periods of transition, the residence was completely demolished; the walls were removed, the windows were barred, and a communist star was attached to the roof pediment above the two-headed eagle of the Albanian flag. As the end of communism drew near, the communists inflicted further destruction on our home out of contempt for our family. In August 1991, after 46 years of continuous suffering and the fall of communism, our family at last returned to the ancestral residence.

The property was officially designated a Category I Cultural Monument during the communist regime that was in power in 1977. When the property was finally legally “returned” in 1994 to its rightful owners, subsequent to the downfall of a regime that unlawfully seized it and bestowed a status upon it during that regime, it should have been reinstated in its original condition and without any limitations. The classification of Status I was carried out within a structure that sought to eliminate all property and property rights; that regime has since been overthrown, and any legislation that violated property rights and was enacted during its tenure ought to be revoked as well.

The restitution of our property was not subject to any deed restrictions, such as being restricted by the Cultural Monument I status. Albania has acknowledged its culpability by returning a private property which had been confiscated, forcibly seized, sequestered, and subsequently pilfered during the dictatorship of Enver Hoxha. However, the laws enforced by the Ministry of Culture, which remain rooted in policies instituted during the communist era, persist in promoting confiscatory methods that are intrinsically and perpetually unlawful and unjust.

Notwithstanding its undeniable cultural significance, the home did not receive government funding for design, construction, or any assistance from government architects or personnel. It was financed through personal funds acquired by an individual, as opposed to funds provided by the government.

The status of Cultural Monument is a mere pretense. If the government sincerely asserts that this property represents a valuable asset for Albania and a cultural treasure, then the ignorance exhibited by the majority of adults and children concerning the historical lineage of Gjon Marka Gjoni is puzzling. Why is the history of the Gjon Marku dynasty and its impact on Albanian history not included in the national curriculum by the government? Why is there no current instruction in the history classes pertaining to the “Kanun of Lek Dukagjini”, the laws of the highlands, and its enduring impact on Albanian culture? Despite this, they persist in designating historical dwellings like the Kulla as cultural landmarks with the intention of sustaining their tourism endeavors, without genuinely acknowledging that the house’s and its owners’ heritage constitutes the pinnacle of Albanian history.

Due to this, the family does not recognize the property’s status, which was established during the communist regime that unlawfully appropriated it; to do so would be an affront to every family member who was killed and suffered as a result of the regime’s atrocities. We neither acknowledge nor recognize any institution or action that was instituted during the communist era. The manner in which government officials and the media are promoting the status as an emblem of immense prestige is an absolute fabrication and a ruse to obscure the government’s infamous ultimate land grab.

It must be at the discretion of the proprietors, and not the Ministry of Culture or government, to determine whether they would like their property to be included in the National Register. In republican or democratic administrations, the standing authority of the Ministry of Culture to retain and/or declare something cultural property without the owner’s consent violates the concept of property rights. Despite the fact that the status was granted during the period when the property was “not owned by the rightful owners,” any statutes imposed on it should be nullified upon the property’s lawful return to them.

Today, the home legally belongs to Kapidan Gjon Marka Gjoni’s surviving heirs, the children of his three sons: Mark, Ndue, and Nikollё.

Posted on February 7, 2024, in Welcome. Bookmark the permalink. Leave a comment.

Leave a comment

Comments 0